Unconventional,

in size and rise

John Fetterman — the large, tattooed ex-mayor of Braddock — shed his comfortable beginnings and traditional office career to campaign for social equality.

Gary Rotstein

grotstein@post-gazette.com

Before a December sunrise, an unusually large man clad in gym shorts despite the 32-degree temperature is walking a few miles on the Great Allegheny Passage trail near the Waterfront.

On most such days, he’d be alone in the dark, immersed in the late 20th-century grunge or heavy metal rock pumping through his headphones — the same music he enjoyed when a young man on track to succeed in an insurance office or other business setting.

But this morning, a month before his inauguration as lieutenant governor, 49-year-old John Fetterman was reflecting upon one of the more uncommon journeys taken by any Pennsylvanian elected to statewide office. Mr. Fetterman, who spent 13 years as mayor of Braddock, is about to rise from leadership of a striving-to-revitalize borough of barely 2,000 residents to a position serving 12.8 million citizens.

The daily pre-dawn walk — part of a healthier lifestyle that over the past 14 months has shed some 150 pounds from the still-imposing Mr. Fetterman’s 6-foot-8 frame — served for one of a series of interviews in which he traced the most influential events of his life.

Those include a best friend’s death in his 20s; mentoring an orphaned, disadvantaged youth to manhood; performing social work with young people in blighted communities he’d never visited; winning his first election by one vote; attracting an outsized amount of media attention for a small-town official; and marrying a Brazilian immigrant who learned of Mr. Fetterman from 2,000 miles away by reading an article in an obscure magazine.

Lieutenant Governor-elect John Fetterman talks to Charles Prodanovich of Trafford, who recognized him while on a walk, Tuesday, Jan. 8, 2019, on the Westmoreland Heritage Trail in Trafford. (Alexandra Wimley/Post-Gazette)

Add those up, and Mr. Fetterman acknowledges with a shrug that his ascent to Pennsylvania’s No. 2 elected office still defies easy explanation. And if fate had changed any one of those prior aspects — e.g., a different young match in the Big Brothers Big Sisters program, a Braddock voter who couldn’t make it to the polls in 2005, another publication catching the eye of his future wife — he doubts he’d be preparing for swearing-in at the state Capitol Tuesday as Gov. Tom Wolf’s second-in-command.

“I’m as mystified as anybody at the way it’s worked out,” said the man who is presumably America’s tallest statewide office-holder with a shaved head, whether a left-wing Democrat like him, a mainstream Republican like his parents or something else.

Mr. Fetterman’s unconventional appearance, including symbolic arm tattoos and a casual wardrobe like that of few elected officials, has been widely noted in national newspaper and magazine profiles. But what’s readily visible is just one uncommon aspect of a man who pronounces himself happy to spend the next four years assisting Mr. Wolf’s agenda — one that largely mirrors his — but who clearly hopes to have greater impact of his own beyond that.

A comfortable beginning

In the first half of his life, Mr. Fetterman had little interaction with poor people, minorities, immigrants or liberal crusaders of the kind he has become.

Springettsbury, the suburb of York in which he grew up, has a median household income nearly 2½ times that of Braddock’s. The central Pennsylvania community’s poverty rate is four times lower, and African-Americans make up about one out of 10 residents instead of two of three, as in Braddock. It’s in an area dominated by conservative Republicans — though by coincidence, Mr. Fetterman’s childhood home is just a few miles from Mr. Wolf’s longtime residence.

Mr. Fetterman describes having had a contented middle-class childhood — one in which he was sheltered from any hardship. The family was headed by a hard-working father who became a partner in a York insurance firm. Financial success enabled Karl Fetterman to support the oldest of his four children in various ways eventually, which is notable in that the next lieutenant governor has not had a traditional job and paycheck in more than a decade. (The mayor’s position in Braddock, from which Mr. Fetterman resigned Dec. 21, pays $150 monthly.) Karl Fetterman has covered his son’s living expenses for years, in addition to generously supporting his statewide campaigns and nonprofit organization in Braddock.

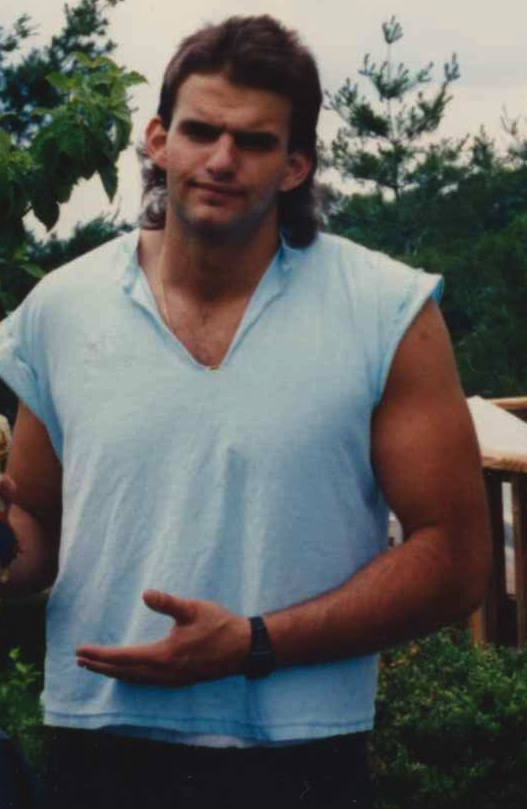

John Fetterman in York, Pa., in 1989. (Photo courtesy John Fetterman)

The most distinctive thing about Mr. Fetterman’s early years may have been his 7-inch growth spurt as a high school sophomore. It led him to become a defensive and offensive lineman on football teams at York Central High School and Albright College in Reading.

Otherwise, he was on a business path very much like his father’s — only one destined for perhaps greater success — if not for two life-shaking events. In the first, when Mr. Fetterman was near completing a master’s degree in business administration from the University of Connecticut in 1993, his 27-year-old best friend died in a car crash when on the way to pick him up for a gym workout.

“It was hard to emerge from that, because it was so sudden, and random, too,” Mr. Fetterman said. “To have this idea that when you’re that age, you can wake up in the morning, have breakfast and kiss your family goodbye and not know that you’ve got 15 minutes left before you get blasted out of this world.”

Ruminating at the time about his purpose in life prompted him to volunteer in New Haven’s Big Brothers Big Sisters program. He was matched with Nicky Santana, an 8-year-old from a low-income Puerto Rican family, whose father had died of AIDs and whose mother was terminally ill with the disease. She pleaded with Mr. Fetterman to look after her son’s schooling.

It is common for Big Brothers Big Sisters relationships to be short-term — especially if one member of the pair moves away, as Mr. Fetterman did after a year together. However, Mr. Santana credits his Big Brother with longtime advocacy and assistance that got him into a New Hampshire boarding school and Washington & Jefferson College. Mr. Fetterman provided him hope, as well as personal financial assistance, from the time of their initial encounter walking around the boy’s poverty-stricken neighborhood to buy candy.

“I get goosebumps now talking about it, what he did for me,” said Mr. Santana, now 33 and working at a New Haven nonprofit that helps people with disabilities. “He had no ties to me. He was keeping a promise to my mother, but he had no reason to do that. He was just invested in my future and helping me become a better person, like we had this mission together.”

One could say the effort Mr. Fetterman invested in that relationship foreshadowed his involvement in Braddock and politics — causes with futures that might have seemed just as bleak as Nicky Santana’s at the outset.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Taking up social work

When Mr. Fetterman first mentored his Little Brother, he had a plum job for his age while wearing a suit every day to the New Haven office of Chubb, one of the world’s premiere insurance firms. Hundreds of other candidates, he says, applied for his position in risk management. In 1995, he gave it up to become a social worker, based on his experience with Nicky.

“It opened up an entire realm of inequality that I never really fully understood existed, and how pervasive it was,” he said. “I couldn’t overcome being preoccupied with the random lottery of birth. I thought about my own childhood, and how I’d ended up with an MBA and security and freedom and flexibility, and how this poor little boy lost both his parents before his ninth birthday.”

Mr. Fetterman renounced everything he’d prepared for until then, taking an AmeriCorps service job with the Hill House Association in Pittsburgh. He provided GED preparation to disadvantaged young parents who had dropped out of high school. He had no connection to his new city before that. His family was fairly stunned.

“He had what I thought was a dream job, handling stuff I’ll never see — major national accounts,” Karl Fetterman recalled. “He said he was going to do social work in Pittsburgh. I kept my mouth shut. I was taken aback, but I also thought it was kind of neat, him giving up this job and big money to do something for people.”

AmeriCorps is a federally backed program of short-term duration for participants, but which provides financial support afterward for post-graduate education. After two years in the Hill District, Mr. Fetterman spent the next two years obtaining a master’s degree in public policy from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, then indulged in the uncertain young man’s cliche of “finding yourself kind of stuff” for two years, Mr. Fetterman now says, sheepishly.

John Fetterman, right, addresses his supporters at his primary election watch party as his wife, Gisele, hugs longtime friend Jovan Villars, 36, of Swissvale on Tuesday, May 15, 2018, at Barebones Black Box Theater in Braddock. (Stephanie Strasburg/Post-Gazette)

That all led to finding himself in 2001 in a job similar to what he’d done in the Hill, only in Braddock this time. He headed the startup of the Allegheny County-sponsored Braddock Out-of-School Youth Program, preparing high school dropouts for GED testing, job pursuits and additional life skills.

One of the first participants, Jovan Villars, remembers Mr. Fetterman providing a “safe haven” in a small classroom in Braddock’s Ohringer Building for young adults escaping troubles at home or on the streets.

By then, Mr. Fetterman’s receding hairline had prompted the once-mulleted man to routinely shave his head. Combined with his size, he freely acknowledges it might cause some people to view him as intimidating, even scary like a “skinhead biker.”

That look was not how he sought to influence his young charges in Braddock. Instead, Mr. Villars said, Mr. Fetterman met the participants on their level, helped line up job interviews, communicated about their troubles while offering hands-on assistance. His demeanor is typically sober and low-key, with a dry sense of humor, unlike the gregarious stereotype of a big man.

Mr. Fetterman also clothed himself typically in jeans or cargo shorts, dark sneakers and Dickies work shirts, attire not much different from what the program participants wore. He’s appeared the same way ever since, including during his statewide campaigns for office.

“He was just relatable, one of the humblest and most personable big guys I’ve ever met,” Mr. Villars said. While Mr. Fetterman’s race and background were different from most participants, “it wasn’t like he was a fish out of water. He was very fluid, able to navigate, because he already had a template from what he’d done with Big Brothers Big Sisters and AmeriCorps and Hill House.”

Mr. Fetterman lasted six years in that job. By then, he’d found another calling in Braddock.

No longer apolitical

Other than serving what he considers an unmemorable stint as a class president at Albright, Mr. Fetterman’s disinterest in elections was such that he has no recollection of voting before his 30s. But in 2005, after working in Braddock for four years and living there for two, Mr. Fetterman ran for mayor.

He didn’t expect to win, he says, but simply sought to call more attention to violence affecting young people in the community. In a three-way Democratic primary, he won by one vote. And even that was a provisional vote — one that could not be recorded until the day after the election, since the voter’s eligibility had to be confirmed.

“That’s an anecdote I relate on the campaign trail to this day to anyone who says, ‘My vote doesn’t count’ or ‘Why should I vote?’ ” Mr. Fetterman says. “I often think of that day, and what would have happened if just one person had said it doesn’t matter.”

In heavily Democratic Braddock, a primary win is tantamount to being elected, and Mr. Fetterman was re-elected to three subsequent terms by comfortable margins. Serving as a borough mayor, however, is not like being mayor of Pittsburgh: A borough manager runs municipal operations and borough council creates the budget.

The mayor is primarily charged with overseeing the police department, but it’s run day-to-day by the police chief. Mr. Fetterman worked with Braddock’s chiefs on community policing initiatives to improve relations with the largely African-American citizenry, but his tenure won the most attention for attempts to rescue the community from post-industrial despair. While a borough mayor can’t do much on his own, Mr. Fetterman built useful partnerships with foundations, businesses and other agencies beyond Braddock.

The collaborations brought additions such as acclaimed dining and drinking establishments; new housing; an urgent care center to replace UPMC Braddock, which closed in 2010 despite protests by Mr. Fetterman and others; urban farms tended by teens; and a community center created out of a dilapidated church renovated by Mr. Fetterman’s nonprofit organization, Braddock Redux.

His efforts were recognized in profiles by The New York Times, Rolling Stone and other national publications. The Guardian dubbed him “America’s coolest mayor.” He was twice a guest on Comedy Central’s “The Colbert Report,” with the studio audience snickering in 2009 when he declared the mere addition of a Subway sandwich shop (none came) would have represented a grand Braddock improvement at the time. Levi’s learned of him and made the town’s gritty look the focus of a national advertising campaign, agreeing through Mr. Fetterman to donate more than $1 million for the community center project.

Along the way, some local sniping materialized that Mr. Fetterman was getting too much personal credit for Braddock’s transition, one in which a lot of work is still to be done. Some black critics suggested that efforts were focused more on white newcomers or visitors than longtime residents.

Mr. Fetterman makes no apologies, stressing that his efforts have never created the kind of gentrification that pushes people out. In his limited capacity as mayor, he said, he simply sought innovative ways to rebuild a community that over decades had lost 90 percent of its population as well as most of its commerce and reputation.

“The thing that most matters is the bully pulpit and the ability to convene and direct attention and resources to people, places and projects that are needed,” he said.

But upon his resignation Dec. 21, he said his greatest satisfaction came not from renewal efforts, but from years when Braddock suffered no homicides. He was most troubled, at the same time, by the 10 killings that did occur during his 13 years.

The first nine are noted indelibly by dates tattooed on his right arm (his left forearm bears Braddock’s 15104 ZIP code). The first date is 1-16-06, which was Martin Luther King Jr. Day that year. Mr. Fetterman, who had been in office two weeks, led scores of volunteers in a holiday cleanup project at the future community center. That night, he was summoned to a police crime scene where a pizza delivery man had been robbed and shot in the head. The shaken new mayor got the tattoo days later.

Tattoos on John Fetterman represent dates of homicides in Braddock when he was mayor.

“I was just like, ‘This is a day I’m going to remember for the rest of my life, something I’m going to carry with me,’ and this man’s life mattered, and he’s going to be quickly forgotten by the general public in terms of news and headlines — and maybe people think like that’s Braddock, what do you expect — but I just wanted to get the date and put it there.”

And he did the same at a Lawrenceville tattoo parlor with subsequent murders, except for the most recent, in June, when he was consumed by campaigning.

Advertisement

Advertisement

An unconventional love story

If he wanted a more positive date in ink, Mr. Fetterman would add 6-9-08, to note when he both became a husband and learned he would be a father.

It was 10 months after the former Gisele Almeida picked up a magazine called ReadyMade while killing time in the lobby of a yoga retreat in Costa Rica. On page 68, she read a story, “Captain of Industry: One Man’s Mission to Save Braddock,” which pictured a large, bald man in shorts leaning on a Lincoln Town Car in front of a weathered building. She tore out the article.

The future Gisele Fetterman, now 36, was struck by how similar the Braddock efforts were to her own aspirations in Newark, N.J. That wasn’t her original home. She was a native of Rio de Janeiro whose mother fled violence there, landing with Gisele, 7, and a son as undocumented aliens in New York City.

Eventually, the family would obtain legal immigration status. Ms. Fetterman, now a U.S. citizen, became a nutritionist focused on anti-hunger projects. Captivated by the Braddock article, she wrote to Mr. Fetterman expressing interest in visiting the community to see the work taking place.

He phoned with an invitation. She spent 24 hours in Braddock in October 2007. They recognized one another as kindred spirits. He visited her in New Jersey. They fell in love. She moved to Braddock the next May. They eloped to Burlington, Vt., that August. She took a pregnancy test on their wedding night. It was positive.

“It was like a big red-letter day, being married and then finding out you’re going to be a father, all within the span of five hours,” Mr. Fetterman says, still astonished by that and the rest of the story — her family’s immigration saga, the random magazine article, the handwritten letter from her, her 355-mile drive to a town with a rough image where she knew no one.

When she asked someone at a gas station a few miles away for directions to Braddock on that first trip, Ms. Fetterman remembers, “He was like, ‘Why do you want to go there?’ I was like, what am I walking into? But adventure runs in my blood.”

At the end of the day on which she met Mr. Fetterman, she curled up on a sofa in his home instead of using the hotel room she’d booked miles away. She was among dozens of people the mayor had hosted at a reception that evening after a Quantum Theatre play at nearby Braddock Carnegie Library. She felt comfortable spending the night, “platonically,” after staying up late talking.

“I just remember thinking this was a very good person,” she said of her first impression. “I just think there’s an unapologetic authenticity about him.”

The couple live in a loft in a former Chevrolet dealership with big windows overlooking the Edgar Thomson Steel Works and now have three children, ages 9 to 4. And Ms. Fetterman has become a force in her own right, co-founding 412 Food Rescue, which redistributes to hungry families usable food that would otherwise have been thrown away, and creating the Braddock Free Store, which provides a variety of surplus and donated goods to anyone in need.

Looking to enhance his role

Mr. Fetterman’s first campaign for statewide office — the initial sign that he had ambition to do something beyond Braddock — came in 2016, seeking the U.S. Senate seat held by Republican Pat Toomey. He finished third in a four-way Democratic primary while receiving 20 percent of the vote.

Though getting fewer than half the votes of party nominee Katie McGinty, who would lose to Mr. Toomey, Mr. Fetterman felt emboldened by his finish, considering his relative lack of funds and name recognition.

That set up last year’s bid for lieutenant governor, in which he sailed to nomination over four other Democrats, including the incumbent, Mike Stack, on whom Mr. Wolf soured early in his first term. As in the failed Senate race, Mr. Fetterman benefited from being the sole candidate from Western Pennsylvania. He also campaigned vigorously in rural counties statewide, he stressed, and believes that a lot of voters were attracted to his Braddock story and his progressive platform, particularly as a response to Donald Trump’s Pennsylvania victory in 2016 and right-wing agenda.

Mr. Fetterman has long backed legalizing recreational use of marijuana and supported a $15 minimum wage, stronger gun control measures (though he owns firearms himself) and other policies more in vogue for years with party leftists than centrists. He was the first in Western Pennsylvania to perform same-sex weddings. His new chief of staff will be Bobby Maggio, a 26-year-old gay man who managed Mr. Fetterman’s most recent campaign.

“The Democratic Party has moved and evolved on the issues to where I was always at,” Mr. Fetterman said. “Everyone’s progressive now. ... There’s a growing wave and momentum in recognizing how severe inequality is in our country.”

It’s that latter point — harking back to his relationship with Nicky Santana — that most motivates him to seek a higher position. Mr. Fetterman bristles at the notion of lieutenant governor being a low-value, low-impact role, though by statute it calls for him only to preside over the state Senate, Board of Pardons and Pennsylvania Emergency Management Council.

He intends for the pardons board to reduce Pennsylvania’s prison population by releasing more inmates who justify a chance in the community. More broadly, he hopes his positive relationship and shared views with Mr. Wolf will win him more responsibility than is typical of the office. At the end of four years, Mr. Fetterman hopes to have a record that would place him in good position to challenge again for Mr. Toomey’s Senate seat, if he decides to pursue it.

J.J. Balaban, a Philadelphia-based campaign consultant accustomed to working for Democrats, including many Pennsylvanians but not Mr. Fetterman, said the new lieutenant governor could face an interesting test, as no one in that position has been elected senator or governor in Pennsylvania since the 1960s.

“Even for someone as distinctive as John Fetterman, he may find the office is not as good of a base as one might think,” Mr. Balaban said. “The challenge of being lieutenant governor is you have basically very minimal actual power and authority. ... Your power is mostly derived from what the governor allows you to do. That said, it’s clearly a bigger base than being mayor of Braddock.”

In addition to a bigger base, there’s a bigger salary. Mr. Fetterman will receive $166,300 annually as the highest-paid lieutenant governor in the nation. His father’s subsidies that have provided the Fettermans a middle-class lifestyle will no longer be needed.

Mr. Fetterman is not, however, moving his family into the state-provided mansion Mr. Stack has inhabited in suburban Harrisburg. He calls Braddock his permanent home, and he will commute for a few days each week in his black pickup truck to a residence in the state capital owned by his brother, Gregg.

And as he did with Chubb half a lifetime ago, Mr. Fetterman plans to wear a suit while performing his state duties. Just don’t expect him to get rid of his Braddock tattoos.

Gary Rotstein: grotstein@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1255.

Advertisement

Advertisement