The mission of the Pittsburgh Steelers Football Club is to represent Pittsburgh in the National Football League, primarily by winning the Championship of Professional Football — first line of Steelers’ mission statement, as told in Dan Rooney’s autobiography.

Winning. That is what I think of first when I think of Dan Rooney. I think of a franchise that couldn’t walk straight for nearly 40 years until Art Rooney Sr., the Chief, finally turned over a coaching search to his eldest son.

I think of those six Lombardi trophies behind glass on the South Side.

I think of Tim Rooney, one of “Danny’s” four brothers — they all called him “Danny” — explaining to me what selling Steelers football entailed 60-some years ago, long before “Steelers Nation” and lifetime waits for season tickets.

“We’d go to all the mill towns — Homestead, Donora, Beaver Falls, Ambridge, everywhere — Danny must have driven us and dropped us off — and we’d stand there with a piece of paper, trying to sell the mill workers season tickets for $16, if you can believe that,” Tim Rooney recalled Saturday. “That’s who was buying tickets in those days.”

I think, too, of Dan Rooney telling me that his sickest feeling in football was seeing the San Diego Chargers’ logo on the field for Super Bowl XXIX in 1995, knowing it should have been his Steelers playing the San Francisco 49ers for the championship.

But mostly, on this day, as Pittsburgh prepares a final goodbye for Dan Rooney, I think of what it must have been like to be a fly on the wall in his Miami Beach hotel suite the morning of Jan. 13, 1969, with the football world still buzzing from Super Bowl III the night before — a game that changed the NFL forever.

Little did anyone know the Steelers were about to change forever, too.

That morning, Rooney introduced himself to Chuck Noll. As the two 35-year-old men chatted, quickly realizing they had much in common, Noll’s wife, Marianne, received an unexpected visitor at her hotel room.

It was Don Shula, whose Baltimore Colts had stunningly lost to Joe Namath (son of a Beaver Falls steelworker) and the New York Jets the previous night. Shula knew he was going to lose Noll, his esteemed defensive coordinator, as well. But he wasn’t going to sit around feeling sorry for himself. He wanted to steer Noll to the right place — and that wasn’t Boston or Buffalo, both of which were interested.

It was Pittsburgh, where the Rooney family was desperate to get it right after decades of nearly non-stop losing.

“Don Shula came into the room,” Marianne Noll recalled Friday, a day after Dan Rooney passed away at age 84, “and he said, ‘If Chuck gets that offer, take it. Take it. They’re good people.’ ”

Maybe too good, in the case of the Chief, who didn’t have much of an eye for choosing coaches. He found guys he could “loaf with,” as Dan would later write, and hired Noll’s predecessor, Bill Austin, sight unseen. All it took was phone-call recommendation from Vince Lombardi.

Dan Rooney was frustrated with the process, surely not imagining that his franchise would become unique among pro sporting enterprises for its ability to identify and support coaches (three in 48 years-and-counting).

“I was trying to bring the Steelers into the modern era,” he would later write, “and I knew the right coach was the key.”

This time, Dan would lead the search after a disastrous 2-11-1 season in 1968. But the Chief still couldn’t resist his impulses. Art Rooney Jr. remembered as much Saturday, saying his father, in the middle of the season-ending team party, asked him to call Notre Dame coach Ara Parseghian.

“I said, ‘Oh, this is going to be embarrassing,’ and my dad said, ‘Look, these guys always have to be looking for their next job. They’re football coaches,’ ” said Rooney Jr., who ran the team’s scouting department. “So I called him and said, ‘My dad told me to call you. Would you like to be a head coach in the pros? The Steelers would like to talk.’ He said, ‘Hey, I have a contract, and I’m living up to my contract, but thank you for calling.’

“After that, he was always nice to me when I’d see him.”

The priority quickly became Joe Paterno, who seriously considered the job but chose to remain at Penn State. Dan Rooney interviewed about 10 candidates in all, most seriously Noll and Cleveland Browns assistant Nick Skorich.

Noll prevailed partly because of his encyclopedic knowledge of the Steelers and the way he was able to convey it to Rooney the morning after such a crushing loss.

It helped that both were from working class neighborhoods and Catholic school backgrounds. And that Noll had mostly known winning while working for Paul Brown, Sid Gillman and Shula. That attracted Rooney and his father, whose team had virtually no acquaintance to winning over its 36-year history.

In the end, the hiring of Noll is a story not unlike other franchise-altering moments in this town, such as the Penguins landing Mario Lemieux or the Pirates landing Roberto Clemente, in that it seemed to be founded at the confluence of foresight, destiny and luck.

Who knows what would have happened if Paterno had taken the job, or if Parseghian had been interested?

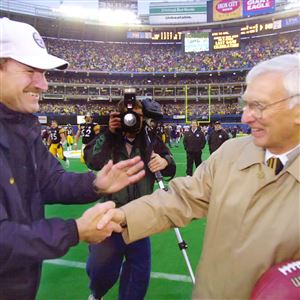

All we know for sure is that in the early morning of Jan. 27, 1969, two weeks after the first interview, Dan Rooney called Chuck Noll to offer him the job. And nobody need wonder where Rooney would rank the move among the thousands he executed in running Pittsburgh’s flagship franchise.

It’s right there in his autobiography, at the start of Chapter 5: “Hiring Chuck was the best decision we ever made.”

It also marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the Nolls and Rooneys (Dan and wife Patricia). Marianne Noll stays in touch with Patricia and spoke with Dan about two weeks ago. She said he mentioned having dinner together soon.

These are difficult days for the builders of the Steelers’ dynasty and their families. Time has proven to be a tougher opponent than the Raiders or Cowboys ever were. Marianne lost Chuck three years ago. She said she misses him every day, though, like all of Pittsburgh, she treasures the memories of those years.

Hers are more personal, of course, and one that stands out is the dinner she and Chuck shared with Dan and Patricia at LeMont atop Mount Washington, the day the Nolls arrived to start their new life.

As described in Michael MacCambridge’s biography of Noll, Marianne “looked out the window to the city lights below and allowed herself to wish. ‘I hope this is forever,’ she said.”

I asked Marianne if she remembered that moment.

“I do,” she said, “And I remember Danny saying, ‘We hope so, too.’ ”

Joe Starkey: jstarkey@post-gazette.com and Twitter @joestarkey1. Joe Starkey can be heard on the “Starkey and Mueller” show weekdays from 2-6 p.m. on 93.7 The Fan.

First Published: April 18, 2017, 4:00 a.m.

Updated: April 18, 2017, 8:58 a.m.